A Lens on Cyprus Reunification

A Lens on Cyprus Reunification

Panikos sat on a beach in Cyprus, dressed in a blue Speedo and straw hat, sipping whiskey with his friends. Behind him, the Mediterranean Sea provided a strangely idyllic backdrop to the topic of our conversation: colonialism, a military coup, and segregation.

“They play with us,” Panikos lamented.

“Who plays with you?” I asked.

“It was the British before, and it is the Turkish now,” he replied.

In 1974, in response to a Greece-backed coup, Turkish troops invaded Cyprus and seized roughly 40 percent of the island. To this day, the country remains divided—ethnically, politically, and geographically. But after nearly half a century, the people want their island back. And that is why I traveled from the U.S. to Cyprus.

I am a Cypriot American anthropologist, and in 2016, I turned my anthropological eye toward my ancestral homeland through a very personal ethnographic expedition. My brother, godbrother, and I walked the circumference of Cyprus—400 miles in 60 days—to gather narratives and images that reflect a multifaceted Cypriot identity. Our goal was to generate a holistic picture of the island’s landscapes, cultures, and people.

We wanted to get past state-sponsored rhetoric, talk to real people living their real lives, and answer one simple question: What unites this divided island?

Cypriots are used to being fought over. Cyprus’ location in the Eastern Mediterranean has attracted nearly every major power in history, from the Mycenaeans to the British Empire. After 82 years of British rule ceased in 1960, Cyprus maintained 14 years of precarious independence. Tensions simmered between the island’s ethnically Turkish and Greek communities, who were then mixed evenly across the country.

These tensions boiled over in 1974. The conflict led to the partitioning of the island into the Republic of Cyprus and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), an occupied territory recognized only by Turkey. The regions are separated by a United Nations buffer zone that spans more than 112 miles and is overseen by one of the longest U.N. peacekeeping missions in history.

Read more about the archaeology of Cyprus’ conflict: “Can the Hunt for Skeletons Help Heal a Nation’s Wounds?”

Today there are few Greek Cypriots in the north and few Turkish Cypriots in the south. Nicosia (also called Λευκωσία in Greek and Lefkoşa in Turkish) holds the unenviable title of the world’s last divided capital. A wall splits the city in two, but the communities on either side share a history, habitat, and infrastructure. Despite these connections, the alienated communities remain unfamiliar to one another. And although there have been many attempts to unify Cyprus, the barbed wire that bifurcates the island holds strong.

Before I started this project, I hypothesized that decades of isolation, alienation, and foreign interference had destroyed any unifying voice in Cyprus. As it turned out, I was wrong.

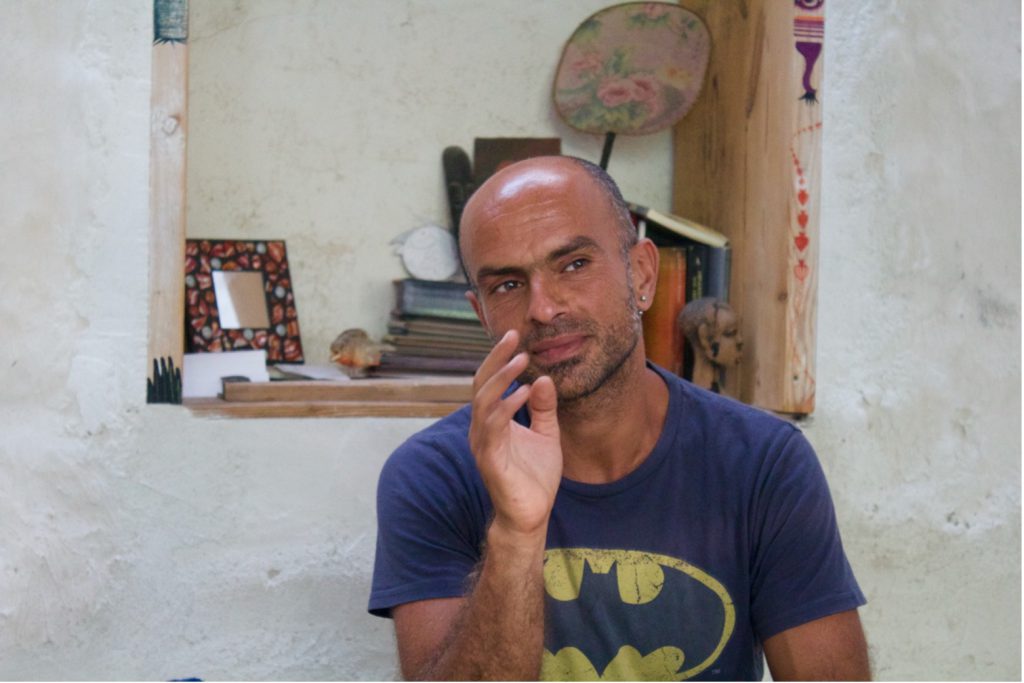

When Panikos and his friends invited us to their weekly beach barbecue, I asked him how he, a Greek Cypriot, felt about Turkish Cypriots. “We are the same people,” he quickly declared. “Even if we do not speak the same language, we find a way to communicate.”

My brother, godbrother, and I interviewed dozens of people during our walk, and we heard this sentiment from nearly everyone. Despite 48 years of division, Greek and Turkish Cypriots consider themselves a single community and desire reunification. The portraits in this photo essay honor the individuals who bravely shared their experiences with us. They highlight the feelings that unite Cypriots and illustrate their persistent capacity for hope.

The island’s prolonged segregation is a cautionary tale for our times. Now more than ever, people around the world are living amid political, economic, racial, and social fracturing. But there is a valuable lesson in these stories from Cyprus. If we look beyond the borders within our own lives, perhaps we will also find more uniting us than dividing us.